Like for the majority of Americans, the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 began as another ordinary day for William Woods Associate Professor of Social Work George Garner. A member of the WWU faculty since 1994, Garner was on his way to work when he happened to run into his wife at the intersection of Nichols and 12th Street in Fulton. She jumped out of her van and yelled to him something that at the time seemed wildly sensational.

The World Trade Center buildings in New York City, she said, had been attacked by planes.

“For me as for many, it was surreal,” Garner recalled. “I spent the majority of the day in Dulany Library watching the news feed and just sitting in disbelief. I remember people in general being uncertain and on edge. The phone lines were jammed and people were having a hard time getting through to their own loved ones. There seemed to be a lot of uncertainty as to what might happen next.”

20 years later, we know what happened next. A horrific terrorist attack on New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Unspeakably nightmarish images of death, destruction and human suffering. Nearly 3,000 innocent people dead. In an instant, a completely changed nation and world.

And little did Garner know at the time, an experience that would end up directly impacting him – and changing his life.

Prior to coming to William Woods, Garner had been employed with the Missouri Victim Center in Springfield, Missouri, working for an agency that provided counseling, therapy, crisis intervention and advocacy for those impacted by violent crime. The agency sponsored Crisis Response Team Training from the National Organization for Victim Assistance (NOVA), and Garner and all employees of the Victim Center were able to attend. Springfield had also developed the Community Crisis Team of the Ozarks (CCTO) which responded to local crimes in the community. A few weeks after September 11th, NOVA contacted the team leader of the CCTO requesting a team from Missouri be assembled and deployed to New York. Given the magnitude of the event, the team leader wanted people with crisis intervention experience, so Garner and one other person from St. Louis were asked to join the team.

Garner and his colleagues were the first team ever from the state of Missouri to head to the New York area after 9-11 and respond at the national level.

Answering the call

The day Garner deployed, in October, he met his other team member at St. Louis’ Lambert Airport, where they flew to Chicago to meet up with others before the flight to New York. The overwhelming emotion he felt was more uncertainty – and even a little fear.

“I remember driving down Interstate-70 early that morning to St. Louis thinking I had possibly made my worst decision ever,” Garner remembers. “I simply couldn’t wrap my mind around the magnitude and wondered how I would be able to offer people in this enormous circumstance anything of value. I felt inadequate about having the skills necessary to assist.”

He remembers looking at planes at the airport and trying to process that these “huge missiles” had actually crashed into some of the biggest buildings in the world, causing their destruction. It all seemed so overwhelming, heading to the scene of such anguish and turmoil. He also had to say goodbye to his family, including young sons age four and five months at the time, for eight days, and secure immediate leave from William Woods.

“The support from my family, friends and William Woods was remarkable,” Garner said. “Lance Kramer (WWU academic dean at the time), never hesitated in saying I needed to go and granting leave.”

And then he was off, heading to the New York City area where the Missouri team would be assigned to the New Jersey Family Assistance Center, working with families who had a loved one who had been employed in one of the World Trade Center towers.

A crisis situation like no other

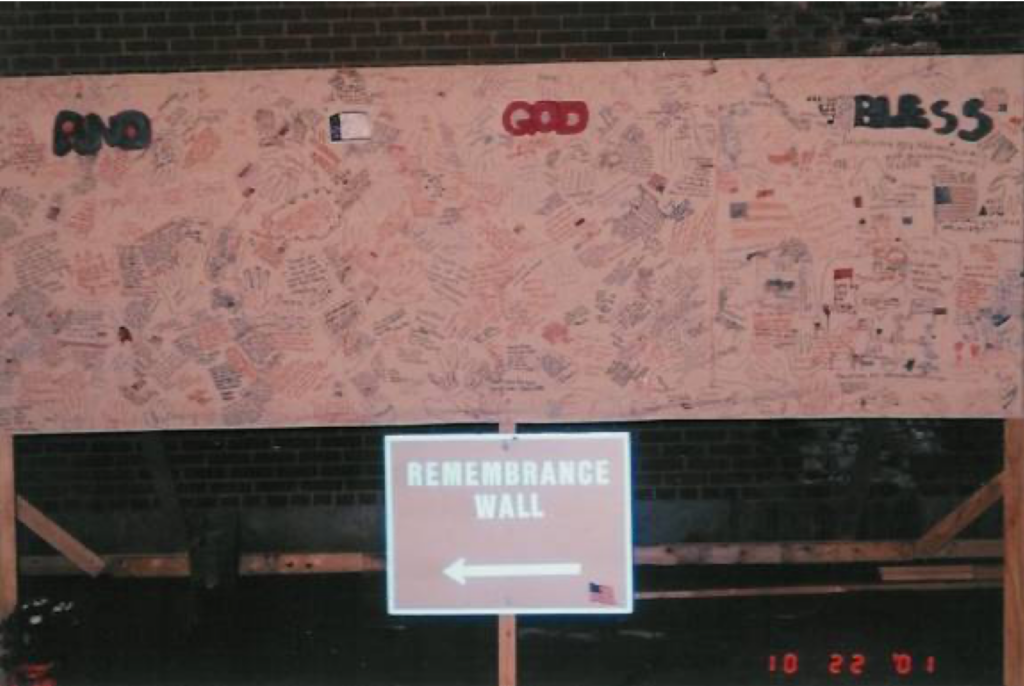

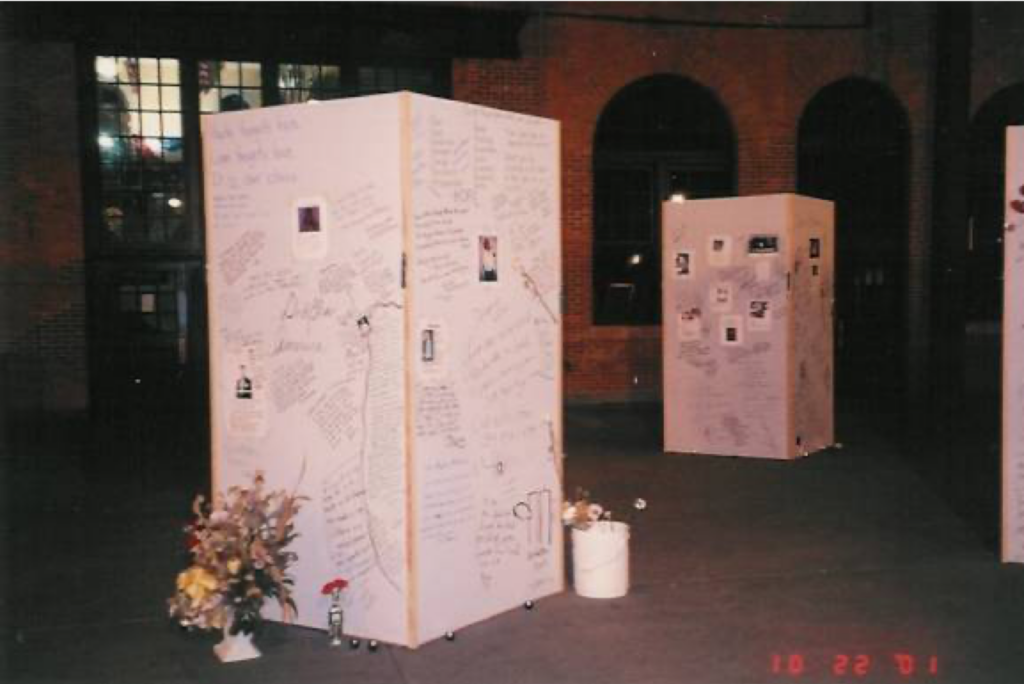

Officials from New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Ground Zero in lower Manhattan, had set up a family assistance center for the responding teams to work out of inside of an old train depot where immigrants had once arrived on boats to then be disseminated into New York City. A beautiful structure that was in the process of being renovated into a museum, the center would serve as a meeting place for family members and loved ones of New Jersey victims to gather before being transported across the river to the Ground Zero site.

“The first morning we walked into the center, there were probably a hundred kiosks set up with pictures of those missing,” said Garner. “the first photo that caught my attention was of a man, about my age, holding an infant child, and I immediately connected with him as a parent of two young boys. I broke into tears, and most of our team members were in tears within the first few minutes. The memorials, pictures and hope of finding their loved ones alive was very powerful. It was good that we had that moment together early on to get us prepared for the days ahead.”

A family viewing platform had been set up at Ground Zero where family members of victims could have their own personal memorial with their loved one. Garner’s team was responsible for contacting families to inform them of the opportunity for the site visit, and to schedule those who wished to participate. While some of his team members made these contacts, other team members and Garner were assigned families to escort to the site. The families would arrive mid-morning, where Garner’s team would meet with them and provide them with whatever they needed to prepare for the visit, go over details, and provide a supportive environment for them. They would eat a meal together, distribute hard hats and masks, then load everyone on to busses to a ferry that would take the group across the Hudson to Ground Zero. It was a two-block walk to the site once they arrived, so the team would provide golf carts or wheelchairs for anybody who needed them.

Once at the site, the group went to the viewing platform where members of Garner’s team remained with families to assist in whatever way needed. They would stay for about 15-20 minutes before reversing the process to return. Back at the center, the team would debrief with each family member until they determined it was time to depart. The next day, Garner’s team would repeat the entire process again for a different group of grieving families.

“I remember each family that I had the privilege of working with,” Garner recalls. “The first family I met had a touching ending as we concluded. I told the sister of the victim that I was a volunteer from Missouri, and she was intrigued that volunteers would come so far to assist. I told her that my employer and my wife were both very supportive, and then we went on with the process of the day. When they were leaving the center at the end of the day, the woman walked away, stopped, and turned to me, saying ‘Please tell your wife thank you for me.’ That was such an incredible moment and one that solidified to me that we were accomplishing our mission.”

Emotions were raw and accessible for everyone Garner encountered, even beyond the families he administered to.

“Everyone was so appreciative and thankful for the support, and many tears were shed,” Garner said. “I will always remember how grateful people were to have others there surrounding them. It was an honor to be part of the whole experience.”

An experience that will always be a part of George Garner’s life. A few years ago, he even met a prospective student and her mother from New Jersey during a campus visit at WWU, where he mentioned his time at the New Jersey Family Assistance Center. They spoke of the talk that one day the center might become a 9-11 Memorial for New Jersey. As they parted, they thanked Garner for being a volunteer and helping during those harrowing days so many years ago.

“I think the biggest thing I took from the experience is appreciating more how we should always let others know that we care about them and love them, and not to just assume they already know,” Garner. “Things changed for many people in that one instant, and we should always remember that we cannot take anything for granted.”

As the nation and world paused to mark the 20th anniversary of September 11, 2001, the memory of what so many heroic volunteers did to help soothe the wounds of countless victims’ family members was once again remembered. But unlike many who took the time to read about or listened to interviews with those who volunteered, George Garner’s experience was different.

He didn’t need to read or watch something to recall what it was like. Because like so many other selfless Americans, George Garner actually lived it.